The unemployment crisis left ignored by India’s budget

Only 40 percent of India's working age population is employed

When India’s finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman got up yesterday to present her fourth and Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ninth Union budget, there lingered a giant elephant in the room–India’s enormous unemployment crisis.

Choosing to remain true to the expression, Sitharaman ignored the scale and size of the problem. The few interventions that she announced are unlikely to address the crisis in any meaningful way.

She looked the other way even as just last week violent protests over the lack of jobs broke out in two of India’s poorest states–Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. (These states are home to over 300 million people and their per capita incomes are lower than some sub-Saharan African nations).

Students, aggrieved by mismanagement and delays in the recruitment process of India’s largest employer, the state-owned Railways, set trains on fire, stormed railway stations and hurled stones. As is par for the course in India today, some students were hounded and beaten by the police.

The cause for their anguish was the botched and delayed recruitment process for 35,000 railways jobs, which these students had applied for.

The next number is perhaps going to give away the level of desperation among the unemployed youth of India today. 12.5 million students had applied for those 35,000 jobs. That’s 357 applications for one job.

That is where the problem lies and why these protests may even be just a pre-cursor to the social unrest that India could see given the massive unemployment challenge that the youth of the country, in particular, face.

That’s the extent of the crisis in the Indian economy. As the chart shows, the situation has deteriorated rapidly in the last decade and it is not only a post-COVID-19 decline.

Less than one in two people of working age are employed. India is doing worse than Pakistan, where 48 percent of the employable population is employed, and Bangladesh, where the figure is 53 percent. China, which India has often aspired to compete with, sits at 63 percent.

The situation is not just bad. It’s terrible. People are not even looking for jobs. That’s captured here by the labour force participation rate, which is a measure of the number of people either employed or unemployed but looking for jobs.

India’s LFPR has been declining for a while now, but the decline has been dramatic in the last few years. Things are even worse than that according to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), which estimates that the LFPR is 40 percent. That means 60 percent of India’s employable population is not in the workforce at all.

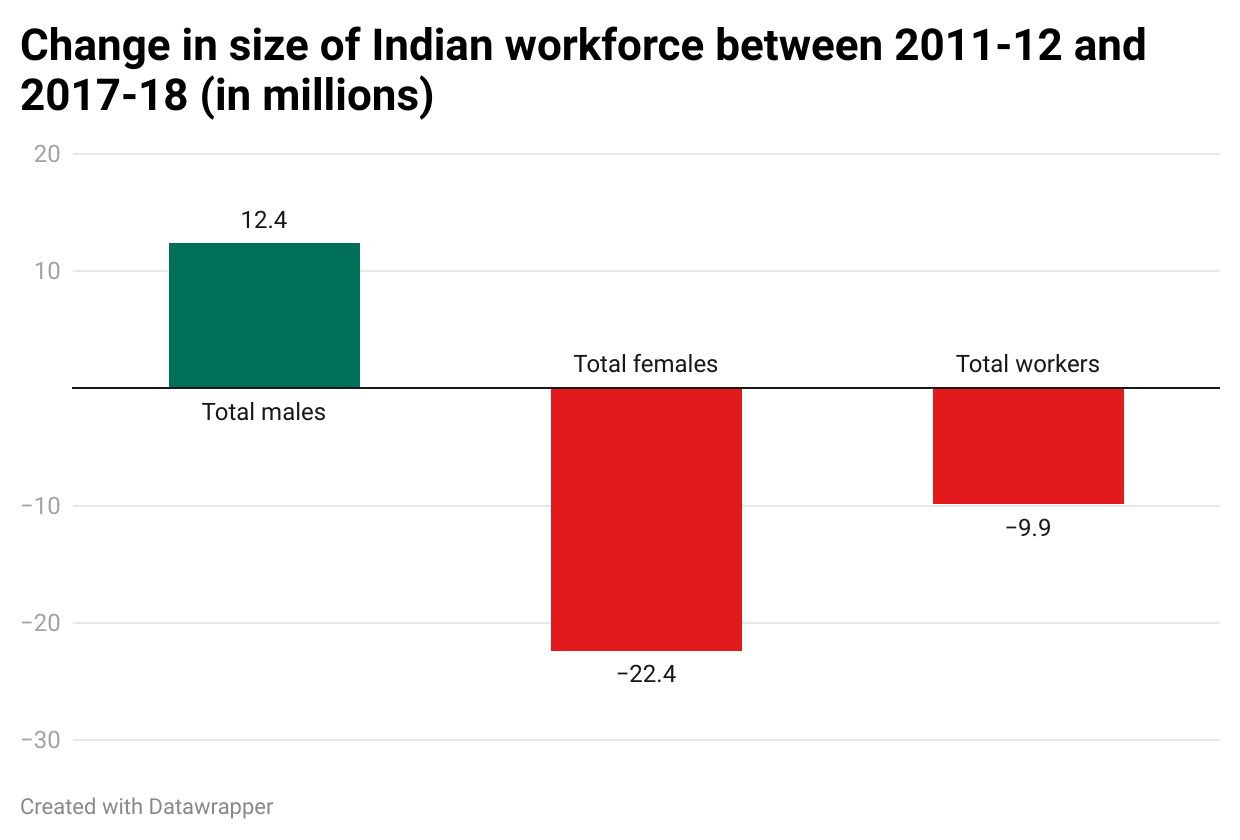

According to an estimate, between 2012 and 2018, India’s workforce shrunk by 10 million, even as the working-age population grew. The overall decline happened despite an increase of around 12 million in the male workforce. So, the female workforce declined by 22 million, a fall of almost 20 percent.

Women’s declining participation in paid work has been a cause for concern for a while. The steep decline began in the 2000s. The downward trajectory has continued and worsened since the pandemic.

According to CMIE data, women’s participation in the workforce is even lower at only 9.4 percent. The monitoring agency has a slightly more stringent definition of what constitutes work.

Although the reasons for this dramatic decline are not entirely understood, some explanations include measurement issues; increasing enrolment in education; increasing household income. Some reasons also point to supply side problems, which mean that there are fewer jobs available for women.

Impacting women the most, total jobs available in India have declined in the last few years. Since 2016-17, India has seen a downturn in economic growth because of the reckless demonetisation experiment which proved to be disastrous.

The botched implementation of the Central Goods and Services Tax (GST) did not help matters and an overall lack of interest of the central government in matters of the economy set India’s growth on a slowing trajectory well before the pandemic.

There are also longer-term, more systemic problems with the kind of growth that India has seen post-1991 when the economy was liberalised. It has not followed the traditional path of structural transformation where employment moves from agriculture to manufacturing.

India saw growth led not by manufacturing, but by services. As a result, India’s growth has not been labour intensive like it was in China. India’s economy grew faster than employment, giving rise to the often-used phrase ‘jobless growth’.

The pandemic has, likes it’s done with almost everything, made the problem worse. India is now doing what no growing economy has ever done. The number of people employed in agriculture has increased after the massive reverse migration that we saw because of the unplanned lockdown imposed by the central government.

More on that later.

Around the World

Concerns are rising in Bangladesh over growing inequality. South Asia’s youngest nation has shown remarkable economic progress in recent years and caused much envy for its neighbours, particularly India. But the growth has not been entirely inclusive with the rich now accounting for a larger share of the national income.

Carbon Brief reports on a new study that finds that black communities in the United States of America will face the largest risks because of flooding.

India’s union budget has fallen short of what needed to be done to strengthen the country’s social welfare systems. This piece analyses the shortcomings in detail.

This New York Times opinion piece argues that wealth inequality is driving the appeal of cryptocurrency.

Listen

The Climate Pod interviewed Peter S Goodman, New York Times’ Global Economics Correspondent, about his new book ‘Davos Man’. The book explains how billionaires systematically plunder the world.